PCE inflation remains too strong in March, but the medium-term outlook is more positive

While the PCE Price Index saw another month of elevated growth in March, a number of key factors are likely to contribute to a significant lessening of price pressures as the year unfolds.

PCE inflation comes in hot in March

For the third consecutive month, PCE inflation came in well above a 2% annualised growth rate, with the headline PCE Price Index (PCEPI) rising 0.32% MoM (3.9% annualised), core PCEPI rising 0.32% MoM (3.9% annualised) and supercore PCEPI rising 0.29% MoM (3.6% annualised). Note that for the purposes of this report, the “supercore” measure refers to the core PCEPI less the housing component.

As a result of price growth remaining elevated for a third consecutive month, the 3-month annualised measures of price growth have surged higher. The headline PCEPI rose to 4.4% (from 3.6% in February), the core PCEPI rose to 4.4% (from 3.7% in February) and the supercore PCEPI rose to 4.2% (from 3.4% in February).

Interestingly, this represents the fastest pace of growth in the core and supercore measures since March 2023, indicating the potential for this latest spike to be somewhat driven by seasonal pressures.

On a 6-month annualised basis, headline PCEPI growth moderated to 2.5% (from 2.6%), core PCEPI growth remained at 3.0% and supercore PCEPI growth remained at 2.4%.

On a YoY basis, headline PCEPI growth rose to 2.7% (from 2.5%), core PCEPI growth remained at 2.8% and supercore PCEPI growth remained at 2.2%.

The convergence between the 6-month annualised and YoY growth rates highlights how the benefit of base effects on lowering the YoY growth has now largely been realised, with further declines in longer-term growth rates now requiring another step down in MoM growth.

While far from certain, with the YoY growth rate stabilising/trending slightly lower in spite of elevated MoM growth to begin 2024, this does provide some indication that the recent spike in MoM growth could be significantly related to elevated levels of seasonality.

While price growth has accelerated early in 2024, there’s plenty of reasons for optimism over the medium-term outlook

Despite a string of hot CPI/PCEPI reports to begin 2024, which have subsequently resulted in market expectations for rate cuts being drastically reduced and bond yields surging higher, it’s not all doom and gloom — instead, there continues to be numerous reasons for optimism surrounding the medium-term inflation outlook.

Some of these key points include:

The BLS’ leading measures of CPI/PCEPI rental inflation continue to point to a major slowdown in rental inflation in 2H24;

Leading indicators continue to point to a significant additional moderation in wage growth, which would be expected to flow-on to a significant reduction in services price growth more broadly;

Wholesale used car price growth continues to point to additional deflation in retail used car prices;

Prior declines in underlying food commodity prices are expected to keep food at home price growth low, and lead to a further deceleration in food away from home price growth; and

While off its lows, M2 money supply growth remains firmly consistent with significant further disinflation over time.

For a very detailed breakdown of these key points (3,500+ words and 50+ charts & tables), including itemised subcomponent forecasts and forecasts for the CPI as a whole out to the end of 2024, please see my latest Medium-Term US CPI Forecast Update.

Looking under the hood

In breaking down the latest PCEPI data, I will segregate the analysis into three components — durable goods, nondurable goods and services.

Let’s firstly begin with durable goods.

Durable goods prices see a third consecutive month of price growth, but it’s important to look at this in the context of broader price declines

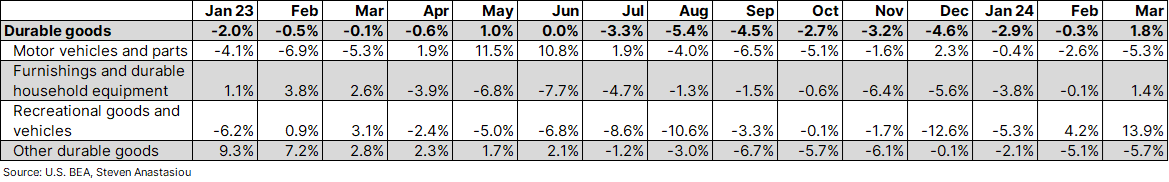

For the third consecutive month, durable goods recorded a MoM increase, but it decelerated to just 0.07% in March (from 0.18% in February).

The deceleration was driven by a large decline in the motor vehicles and parts component, which declined by 0.57% MoM. All other key subcomponents recorded MoM growth. The key item to note here was another material increase in the recreational goods and vehicles subcomponent, which while decelerating from very strong MoM growth of 1.2% in February, still recorded growth of 0.45% in March. This marked the third consecutive month of growth, with computer software prices again recording significant MoM growth.

The increase was also driven by an abnormally large increase in the recording media line item, which saw a huge 12.5% MoM increase that was driven by a 14.7% MoM rise in the video discs, tapes and permanent digital downloads category. While a volatile category, this is far and away the largest increase in the history of this line item (which dates back to February 1977), suggesting that MoM growth should see a material deceleration in the months ahead.

Turning to the 3-month annualised change, overall durable goods price growth turned positive for the first time since May 2023, rising to 1.8% (from -0.3%).

Growth has been driven by the above mentioned recreational goods and vehicles subcomponent, which surged to 13.9%. Though with MoM price growth moderating in March, and January’s very large increase of 1.6% set to fall out of the YoY equation, the 3-month annualised growth rate may moderate significantly in April and May.

All other subcomponents are either recording modest growth or are continuing to see significant price declines, which mitigates the significance of the MoM growth that was recorded by the furnishings and durable household equipment, and other durable goods subcomponents in March.

Out of the entire durable goods basket, the trend in computer software prices during 2024, is perhaps the only item that sparks some notable concern.

Turning to a slightly longer-run trend, 6-month annualised price growth remains negative at -1.4%, but less so than February’s growth rate of -1.8%. Price growth remains negative across all durables subcomponents, highlighting the broad based nature of the longer-run deflation in durable goods prices.

This also helps to put the recent shift to 3-month annualised inflation into broader context, as it highlights how this shift has followed a period of significant price declines, meaning that shorter-run periods of durable goods price growth should not be unexpected.

With the M2 money supply remaining constrained and wholesale used car prices still recording larger YoY declines, I don’t expect the recent increase in durable goods prices to turn into a more significant inflationary upswing.